The company plans to retire Internet Explorer 11 next year, putting it on the path to a long, slow lingering death as the company fully embraces Microsoft Edge.

Microsoft has spelled out its plans to retire the venerable Internet Explorer 11 (IE11) browser from widespread use in a little over a year.

“The future of Internet Explorer on Windows 10 is in Microsoft Edge,” asserted Sean Lyndersay, an Edge program manager, asserted in a May 19 post to a company blog. “With Microsoft Edge capable of assuming this responsibility [of accessing IE-based sites and apps] … the Internet Explorer 11 desktop application will be retired and go out of support on June 15, 2022, for certain versions of Windows 10.”[ Related: Chrome vs. Edge vs. Firefox: Which is the best browser for business? ]

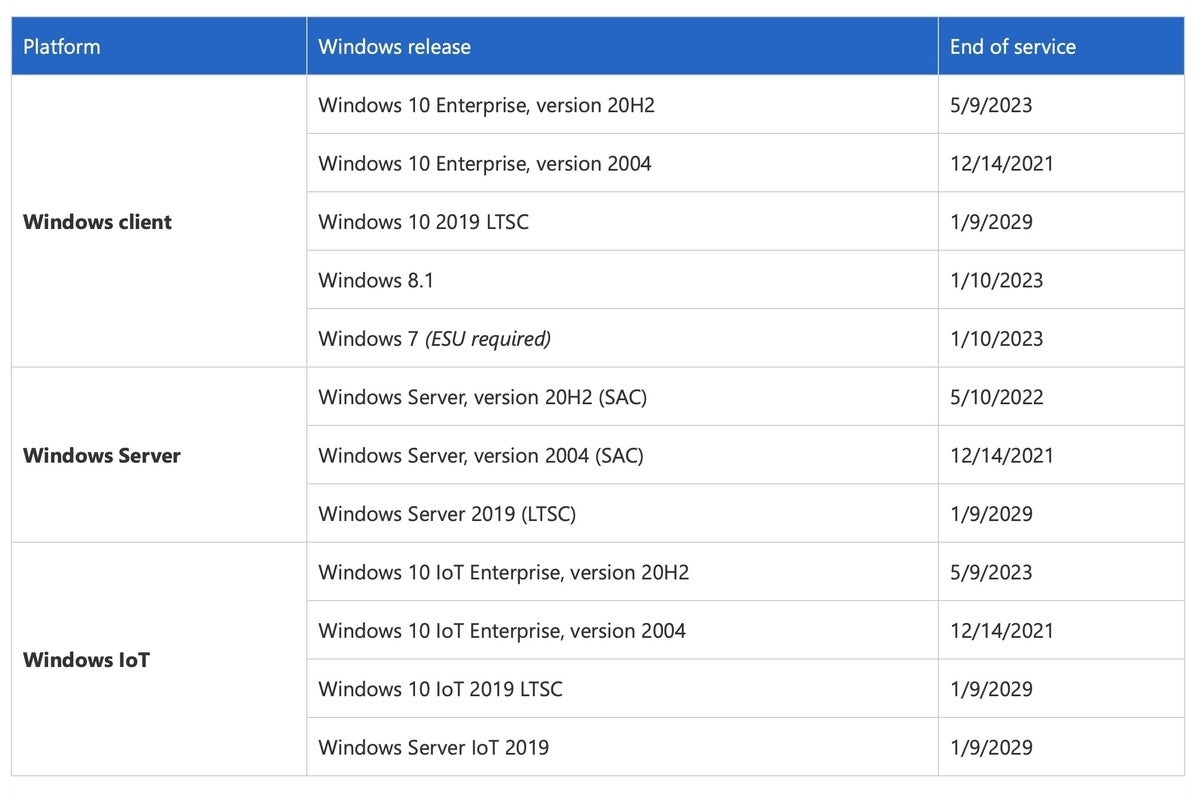

The forced retirement of IE11 — the only version still supported — will not be all-inclusive, as several editions of Windows, including 10’s Long-term Support Channel (LTSC) and Windows Server, will be spared from the directive. Likewise, Microsoft will continue to secure IE’s Trident rendering engine, which is embedded in Windows and crucial to the running of Edge’s IE mode.

Death by a thousand cuts

If it seems Microsoft has been killing IE for years, well, it has. The Redmond, Wash. developer put IE on life support more than five years ago, when it halted development of the browser in early 2016. And once Microsoft released a reworked Edge, the one built atop technologies from the Google-dominated Chromium project, it was only a matter of time before the company pulled that support plug.

Even so, IE11 will suffer a long, lingering death. June 14, 2022 — 12 months and change away — won’t be the end of the browser by any means.

Because Microsoft had previously promised customers that IE11 would be supported as part of the three Windows 10 LTSC versions released so far (the first two, 2105 LTSB and 2106 LTSB, went by Long-term Support Branch) the end-of-support order won’t be applied to them. That’s not to say the separate IE11 application will survive that long. (Windows 10 2019 LTSC, for instance, has support until January 2029, while 2015 LTSB and 2016 LTSB will be supported until October 2025 and October 2026, respectively.) Microsoft alluded to as much when it said that the LTSB/LSTC versions were “out of scope at the time of this announcement” (emphasis added) of the June 15, 2022, date.

Even IE11 running on Windows 7 will be supported longer than next June. Commercial customers who pay for the third year of Extended Security Updates (ESUs) will receive support for IE through the end of that contract, or until Jan. 10, 2023.

IE mode, Edge’s secret weapon

What’s most important to enterprises is that the June 2022 support deadline can be sidestepped by using Edge and its IE mode; that last calls up designated sites using IE’s Trident rather than Edge’s now-native Chromium. (When Lyndersay referred to “the future of Internet Explorer is in Microsoft Edge” (emphasis added, he was referring to IE mode.)

Businesses still wedded to aged internal sites and too-expensive-to-rewrite apps are to be pushed toward Edge and its baked-in IE mode. Not surprisingly, then, support for IE mode will run much longer, until 2029 for Windows 10 2019 LTSC and until May 2023 for Windows 10 Enterprise 20H2, which launched late last year. “IE mode support follows the lifecycle of Windows client, Server, and IoT releases at least through 2029,” Microsoft wrote in a FAQ on the demise of the IE11 desktop app.

By putting a nail in IE11’s coffin, Microsoft means to provide its Edge browser with, well, an edge. At least since Chrome’s appearance in 2008, and to some degree even before that because of Mozilla’s Firefox, Microsoft has seen its browser dominance — once overwhelming — deteriorate as customers, first consumers and then later, enterprises, defect to rivals because IE was mired in its backward compatibility and simply could not compete. IE was old, relied on old technologies and was, at best, a kludge that creaked and groaned whenever it faced the web as the latter changed into a media-rich ocean of content.

Edge, launched in mid-2105 as part of Windows 10, was Microsoft’s attempt to stem the bleeding of browser share. That didn’t work. Even with Edge and IE combined, Microsoft’s share kept dropping. So Microsoft abandoned its own rendering and JavaScript engines and swapped in Google’s instead, relying on Chromium’s open-source nature, like other browsers before it, to become a clone of Chrome. Since then, Edge has edged up in share; as of April, it accounted for nearly an eighth of all browser activity.

It’s virtually certain that much of that growth has come from Microsoft’s best customers, the businesses, small and gigantic, that run on Windows. Some of those companies still required IE so that employees and partners could access old, very old in some cases, intranet sites and apps. IE mode made the back-and-forth between Edge and IE renderings, if not automatic at least configurable.

That was an advantage over Chrome when Google’s browser was adopted by IT administrators. Google had, of course, countered with what it dubbed “Legacy Browser Support,” or LBS, which was originally a browser add-on, then in 2019, integrated with Chrome itself. When faced with a URL designated as requiring IE, Chrome called up IE to paint that page. It was an inelegant solution that, unlike Edge, resulted in two open browsers.

The disappearance of IE11 — enterprises won’t want to use the application once security updates dry up next summer — means that Chrome won’t be able to handle the IE-dependent URLs and apps.

Or does it?

Last month, Google said that Chrome 90 — the version that launched April 14 — could use LBS to open Edge in IE mode instead of opening IE11. “With Chrome 90, we now support configuring your environment to switch between Chrome and Microsoft Edge in IE mode,” Google said in the browser’s enterprise release notes. (More information about configuring LBS for Edge in IE mode can be found here.)

Almost certainly, Microsoft gave Google a heads up that it was getting ready to ditch IE11 and leave Edge’s IE mode as the sole legacy solution.

The difference between then and now for Chrome and its LBS — then when Chrome opened IE and now, when Chrome opens Edge instead — is significant. Users would not have done more with IE than they had to; remember, it was old as Moses and crippled when compared to a modern browser. But Edge? That’s going to be different.

Once open, Edge may tempt Chrome users into staying with it, running it for more than rendering IE-reliant sites and apps. Edge may appeal to Chrome users — the former is the latter, more or less — enough, anyway, for some to wonder why they’re running two browsers when one will do.

We’re not saying that this was the only, or even most important reason Microsoft decided to finally kill IE11. (Microsoft’s Lyndersay ticked off several in his post, but they were largely boilerplate arguments about Edge’s superiority.) Internet Explorer long outlived its usefulness and its sell-by date, technology-wise, wasn’t long after its October 2013 release. If not for Microsoft’s indulgence of its commercial customers and the company’s history of backward compatibility and support, IE should have vanished around the time Edge came on the scene. (Such a drastic move couldn’t have injured Microsoft’s browser share any more than the company’s actual actions, notably its 2014 decision to force users to upgrade IE, which kicked off Chrome’s surge starting in early 2016.)

But if IE11’s demise helps out Edge, at least Internet Explorer succumbed for a good reason. Few browsers can say as much.